In our February 2025 Observation piece ‘The New Great Game’, we wrote at length about the historical context and secular forces driving the rapidly changing global geo-political environment. In our discussion, we explored several high-level investment implications as the world shifts away from the Pax Americana period of the 1990s.

We continue to believe that the world is transitioning to sustained multi-polarity. In this Observations piece, we unpack some of the accompanying fundamental macroeconomic changes which we believe will likely occur over the next 5 to 10 years should our thesis take hold. Broadly speaking, we see the potential for a significant recalibration in global trade and capital flows which could have profound longer-term implications for investors. BCA Research calls this the “Great Rebalancing”. JP Morgan Asset Management concurs with this thinking by flagging a potential narrowing in the US’ historical exceptionalism relative to the rest of the developed world. In our discussion, we start by laying out the current state of global trade and capital accounts, highlighting how we got there, as well as the key imbalances influencing the world today. We then consider how these imbalances might evolve in coming years and discuss the implications of this ‘recalibration’ of the global economy for investors.

The current state of global trade, economic, and capital dynamics can be summarised along four key themes:

1. China over-produces and under-consumes

2. Europe under-spends and under-invests in its economy

3. Other major emerging markets (India, Latin America etc) compete for foreign capital to fund internal development

4. All of the above rely on the US to act as the global consumer of last resort and purchase what they produce.

These dynamics have broadly framed the global economic and market paradigm over the past few decades and ultimately stem back to the US’ decision in 1945 to underpin the global monetary and economic system. In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the US economy held the lion’s share of global economic activity, wealth, and intact capital stock. As US policymakers surveyed the devastation of post-war Europe and turned their minds towards their imminent existential struggle with the Soviet Union, they adopted a ‘deliberately altruistic’ foreign policy strategy. First, via the famed Marshall Plan, the US invested heavily in the reconstruction of Europe (with little expectation of repayment) and supported the ongoing integration of the European continent as a bulwark against the Soviet Union. Second, the US leveraged its post-war hegemony to transition towards a more credit-funded, consumer-driven economy. This served the dual purpose of 1) improving Americans’ standard of living and 2) supporting the development and economic growth of US allies and trading partners by purchasing their excess production. Third, the US military served as the West’s policeman, underpinning global geo-political stability, enforcing the US-designed rules-based international framework, and allowing US allies and trading partners

to focus on developing their own economies and pursuing comparative advantage to the benefit of the broader global community. US allies have adopted the US dollar and US Treasuries as the global reserve asset, recycling their trading surpluses back into the US. In addition, nations outside the Soviet sphere also effectively agreed to broadly follow the US lead on global matters. This virtuous cycle persisted for decades and supported the incredible period of economic, cultural, and human development the world has experienced since 1945. It also led, directly and indirectly, to the four key themes (above) that define today’s world. Since its accession to the World Trade Organisation in 2001, China’s heavily export- and investment-oriented economy has transformed it into the world’s factory, enriching its economy by producing and exporting all manner of tradeable goods. While this has made China a leading industrial superpower, it has also heavily exposed its economy to global trade cycles and has resulted in a gross over-investment in fixed capital ie China has built too many factories, mills, smelters etc.

Meanwhile, other major emerging markets (think Brazil, India, Indonesia etc) have generally faced large capital needs to fund the development of their economies over recent decades – unfortunately, they had neither the post-war largesse of the Marshall Plan, nor the significant domestic savings and state-directed nation building plans of China to help finance this. Instead, they rely heavily on foreign direct investment (FDI) primarily from the private sector (corporations and investors). This exposes these emerging markets to global investor sentiment, global liquidity conditions, and global interest rate shifts. The traditional investment heuristic that a weaker US dollar benefits emerging markets and vice versa is directly linked to this dynamic – as the global reserve (and funding) currency, a stronger US dollar imparts higher costs of capital for emerging markets, dragging on their growth and potentially sparking capital flight out of emerging markets.

The Eurozone has generally been constrained by the mismatch of having a single currency and central bank while maintaining separate national budgets and fiscal policies. As a result, it has had great difficulty crafting a unified policy response to internal or external challenges. German fiscal conservatism has generally hamstrung unified fiscal responses to the GFC, the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis of 2011–12, and even the post-COVID EU Recovery Fund. Because of the intransigence of its largest economy, Europe in aggregate underspends fiscally and underinvests in its economy relative to the rest of the world. While peripheral Eurozone economies have been more fiscally profligate (think France, Greece etc), the lack of fiscal support from the Teutonic centre has led to sluggish underlying demand area-wide and made Europe reliant on external trade and demand.

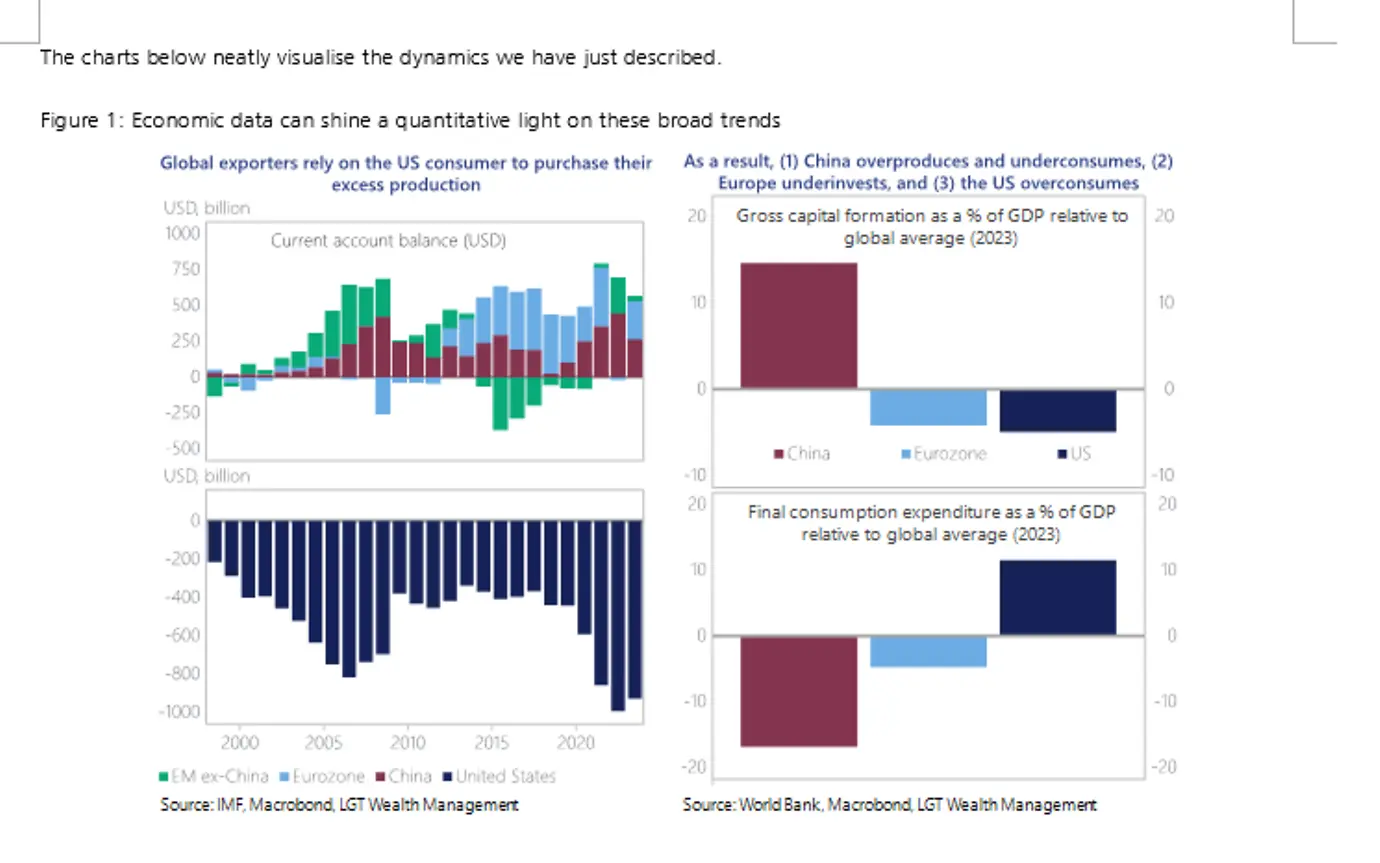

We have established that China (over-produces and under-consumes), Europe (under-spends and under-invests in its economy), and other emerging markets (compete for foreign capital to fund internal development) are dependent on external demand to support their economies. For decades, the US consumer has proven to be the major, and in some cases, sole source of this external demand. For context, the US consumer (about 4% of the world’s population) makes up about 30% of global consumption expenditure, with this persistent demand providing the rest of the world with 1) a customer to buy all the goods and services they produce and 2) a deep, liquid market to recycle this capital. As our explainer box below outlines, these broad trends can be quantitatively tracked over time by analysing global current and capital accounts. Through this lens, we can see that China and the Eurozone have run consistently large current account surpluses over time as they export surplus production overseas, while the US runs consistently large current account deficits as it consumes this excess production. Other emerging markets have had generally mixed dynamics as they either jump on the China/Europe export bandwagon (such as the Asian Tiger economies) or import capital to fund internal development.

LGT Explainer: Current accounts, capital accounts, and why they are mirror images Every country’s national accounts contain two intertwined ledgers that together form its Balance of Payments:

▪ Current account – the current account measures the balance of exports and imports of goods and services and international transfers of income (such as dividends, interest, and foreign aid). A country with a current account surplus exports more goods and services than it imports, earns more income from overseas than it pays out, or a combination of the two.

▪ Capital account – the capital and financial account measures the net balance of sales and purchases of assets and liabilities, including fixed assets (like foreign direct investment) and financial assets (such equities and bonds). A capital account surplus indicates a country is experiencing an inflow of capital, as foreigners are purchasing more of its assets. In contrast a capital account deficit capital is flowing out of a country on balance, suggesting it is increasing its ownership of foreign assets.

Within the double entry accounting system of national accounts, the current account must (by definition) exactly offset the capital and financial account. In other words, a country with a current account surplus must have a corresponding capital account deficit. In effect, this country is receiving surplus income from the goods and services it exports and is recycling that income into acquiring foreign assets.

The charts below neatly visualise the dynamics we have just described.

Figure 1: Economic data can shine a quantitative light on these broad trends

The flipside to a current account deficit is a capital account surplus. In other words, while the US has been importing more than it exports to support its consumption-driven economy, it has also seen consistently strong inflows of foreign capital over the years. As of Q2 2025, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that foreign investors hold about USD 66 trillion of US assets, including significant holdings of US Treasuries, corporate debt securities, and equities. In effect, as foreign countries receive excess income from their exports to the US, they recycle that income back into US assets. This inflow of foreign capital has helped the US build the deepest and most liquid capital markets globally and made it the world’s number one destination for foreign investment.

We acknowledge the currently heterogeneous and more fragmented nature of emerging markets outside of China but for the sake of brevity, we will limit the scope of our analysis to the three major regions of China, the Eurozone, and the US. Within this group, we see three major macroeconomic imbalances – China over-invests and under-consumes, Europe both under-invests and under-consumes, and the US over-consumes and under-invests. These imbalances have existed for many years, so why should investors pay attention to them now? We see two key reasons why:

On the first point, much has been said and written about the generational levels of inequality and inequity within the US and how this has fomented now-extreme levels of political polarisation and populism within America. In a nutshell, post-war US consumption growth initially supported both domestic manufacturing and services sectors, and promoted improving living standards as TVs, refrigerators, air conditioners, and automobiles permeated the landscape. However, most of the ensuing capital account flows into the US were invested into asset markets, so shareholders and wealthy investors actually derived the greatest economic benefits as asset values grew well in excess of broader wage or economic growth. Meanwhile, offshoring production overseas to lower cost jurisdictions led to a hollowing out of the manufacturing sector in the US, leading broadly to the social and political situation the nation finds itself in today.

China, the main beneficiary of this offshoring, has not been unaffected by these imbalances. Global investors will be familiar with China’s various external practices (including deliberate management of its currency) that have been branded ‘unfair’ by other trading partners. Internally though, driven by various cultural and historical reasons, Chinese consumers’ chronic under-consumption has limited the growth of its domestic services sector, which has led to a lack of employment opportunities, particularly for China’s youth. China’s statistics bureau stopped publishing youth unemployment rates when they hit a record-high 21% in 2023 – it has since released a revised measure that is currently around 19%. This compares to around 11% in the US and around 14% in the Eurozone. Meanwhile, a lack of familiarity with financial markets and state-imposed capital controls has seen Chinese households funnel their significant excess savings into the domestic property market. The bursting of China’s housing bubble in 2021 has severely damaged confidence amongst China’s consumers and made them even more hesitant to spend, further aggravating the lack of consumption in the economy. The end result? A household balance sheet crisis that China is still working through, an economic model dependent on the US consumer to purchase its excess production, and an ongoing drip-feeding of stimulus as authorities attempt to balance debt levels, social pressures, and longer-term economic transformation plans.

In Europe, a similar export-dependent economy coupled with Germany’s long-standing inclination to fiscal austerity and a lack of area-wide fiscal consolidation has also hollowed out its economy, hampered consumer sentiment and spending, and led to significant internecine tensions within the Eurozone. Rolling political crises have hit Greece, Italy, France, and Germany over the past 15 years, and the continent has seen a sharp rise in political extremism not dissimilar to the dynamics within the US.

Finally, in terms of the geo-political compact underpinning Pax Americana, the clearest example of this is Saudi Arabia’s longstanding petrodollar arrangement with the US. In the 1970s, Saudi Arabia committed to pricing its global crude oil exports in US dollars, the proceeds of which it recycled into US Treasuries. In addition, the US also guaranteed its security through arms sales and military protection. This quid-pro-quo arrangement helped ensure US dollar dominance within the global trading system and underpinned strong demand for US assets, in particular US Treasuries, supporting the US government’s fiscal priorities. A broadly similar historic pattern can be found in the US’ trading relationship with both the Eurozone and China.

This hitherto stable ‘understanding’ is now changing, as internal social tensions strain US, European, and Chinese society, and the world transitions to multi-polarity. Nations are diversifying their trading relationships, investment partners, and reserve allocations, in many cases away from the US. There is more global pushback to US-led initiatives, and in recent years the US itself has been pulling back from the very global organisations and frameworks it created and labelling them “unfair”.

We believe the current state of global trade and capital flows is no longer compatible with the political and geo-political reality of the multi-polar world we now find ourselves in. If our thesis is correct, the consequences are globally profound – if nothing changes, then political and social cohesion within the US, Eurozone, and China, not to mention broader global stability, face existential jeopardy over the next 5 to 10 years. Thankfully, the economic prescription for this malady is surprisingly clear-cut, though radical changes will be required. Simply put, the world just needs to ‘remedy’ these mathematical imbalances:

Economic prescription

We are far from the first commentators to make these observations. BCA Research has written extensively about this topic in recent years. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) made explicit recommendations to help address these imbalances in its July 2024 External Sector Report. In September 2024, Former European Central bank President Mario Draghi published an in-depth and comprehensive report and recommendations for addressing the Eurozone’s imbalances and improving competitiveness.

In China, stimulus efforts over the past 18 months have generally pivoted towards promoting consumer activity and services consumption, eschewing the prior route of property development and fixed asset investment. These include multiple consumer goods trade-in programs for old home appliances and electronics, interest subsidies on loans for large purchases, and promoting the ‘experience economy’. We also expect that further stimulus measures are likely to eventually include direct fiscal payments to consumers, à la the US stimulus checks of the COVID era. China’s anti-involution strategy, also launched in 2025, is also intended to address and eliminate over-investment across its economy.

In Europe, Germany amended its Constitution early in 2025 to abolish its self-imposed ‘debt brake’ and has committed to substantially increasing its fiscal deficit over coming years to fund defense and infrastructure investment. Other Eurozone nations, including Italy, have generally followed suit. It is hoped that this increased public investment can spur a Keynesian multiplier effect by boosting corporate and consumer confidence and improve productivity growth over time.

In the US, we have long held a counter-consensus view that the One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB) is actually more akin to an ‘austerity budget’! Indeed, the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office has projected that once expected tariff revenues are included, the net impact of President Trump’s fiscal and trade policies on the US budget position is actually contractionary over the next 10 years. Of course, this is predicated on the Supreme Court not striking down Trump’s reciprocal tariffs. Regardless, a key practical consequence of Trump’s trade policy thus far has been a (nascent) narrowing in its current account deficit. More broadly, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has espoused a “3-3-3” strategy which aims to stabilise the US debt load by improving real GDP growth to 3%, producing an additional 3 million barrels of oil a day, and reducing the US budget deficit to 3% (from around 6% today). Whether or not this can actually be achieved, there is growing policymaker and voter support for some form of fiscal consolidation in the US. This would reduce aggregate demand in the economy and help reduce the US current account deficit.

Taking a wider perspective, as the global community walks further down the road to multi-polarity, shifting trading and investment patterns, including aspects like the diversification of global reserves away from the US dollar into gold, will further reduce capital flows into the US, consequently lowering its capital account surplus and its current account deficit. All of these changes have occurred within the past few years and appear to radically conflict with our established understanding of how China, the Eurozone, and the US are ‘meant’ to operate. There is a healthy amount of doubt and skepticism amongst the broader investment community as to whether these shifts can endure. We think this nihilistic mindset is outdated and stuck in the past.

Based on our analysis, not only can these shifts endure, but we also believe that they must endure! The ongoing survival and progress of China, the Eurozone, the US, and the broader global community depends on these three great powers addressing their long-seated imbalances and, by hook or by crook, via collaboration or co-opetition, recalibrating the way the entire global economy operates and interacts. This does not have to happen overnight and could very well take most of our lifetimes to fully come to pass. Nevertheless, we believe that the alignment of historical, social, and geo-political forces are driving us conclusively towards a new, more balanced global economy which may look drastically different to the one we currently know.

What does all of this mean for financial markets and investor portfolios? If sustained, these changes should lead to:

Broadly speaking, these potential shifts in economies and markets are aligned with our secular outlook, articulated in our October 2023 Observation piece “Asset Allocation in a Changing World”.

We outline below several key risks to our thesis around the recalibration of the global economy and its investment implications:

The current state of global trade, economic, and capital dynamics can be traced back to the legacy of World War II and Pax Americana where the US helped rebuild a war-torn world and underpinned global demand. In exchange, the world adopted the US dollar and US Treasuries as the global reserve asset.

This led to a build-up of significant global imbalances that are rapidly approaching inflection points: China over-invests and under-consumes; the Eurozone under-invests and under-consumes; the US over-consumes and over-spends. The accrued impact of these trends is fracturing the social contracts within each region, severely straining domestic political stability.

The solution? China must encourage greater consumption; Europe must adopt more active fiscal policy and continue integrating; The US needs to spend less and repair its fiscal position. If these trends play out, we expect economic growth momentum shifting outside the US, providing supportive relative tailwinds for ex-US assets, as well as a weakening of the US dollar and a higher term premium for US Treasuries.

Astute investors should consider an ‘appropriate’ exposure to US assets going forward, be on the lookout for opportunities elsewhere, make sure they are properly diversified, and stay constructive!

Receive ongoing access to LGT Wealth Management’s insights and observations - a curated stream of thought leadership, market perspectives, and strategic updates designed to inform sophisticated investors.