Within the energy transition debate, an area of particular contention is commodities – those who mine them, process them and ultimately use them in their products.

Both mining and commodity processors are insignificant in size across our sustainable portfolios, due to the poor quality they tend to exhibit through a financial lens, the well-flagged environmental damage records and the history of corruption, human right abuses and political instability across some of the world’s largest producers.

Nevertheless, whilst exposure to miners and processors is relatively small, our sustainable portfolios are full of companies which purchase and consume the end product. We must therefore endeavour to understand and mitigate these supply chain risks whilst ensuring these same companies are exercising their influence to transition the commodity market to become more sustainable over time.

It is widely understood that, with a transition of the global economy from fossil fuels to renewable sources of power and electricity, it will require an increasing level of demand and reliance on key commodities, including copper, nickel and lithium.

The International Energy Agency suggests that reaching the goals of the Paris Agreement (stabilisation at well below a 2°C global temperature rise vs pre-industrial levels) would mean a quadrupling of mineral requirements for clean energy technologies by 2040. The expected demand from any of these commodities is set to grow exponentially over the coming decades, highlighting the need for companies to invest in new assets and break more ground.

There is no debate that we need greater supply, both to address critical needs but also to ensure an economically viable transition can take place. The contentious issue that remains is that miners have historically left a path of destruction in their wake, destroying sites of historical significance and, in many regions of the world, use both forced and child labour to extract materials.

The issue is not what they are doing, it’s how they are doing it.

A large part of the issue is down to where these critical materials are found. Most of the minerals we need to facilitate the energy transition come from politically instable areas of the world. 70% of cobalt mined globally takes place in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, most platinum comes from South Africa and most of the world’s copper comes from Chile. This presents a big issue for investors and is difficult to tackle without international cooperation; nevertheless, companies themselves can exert significant influence too.

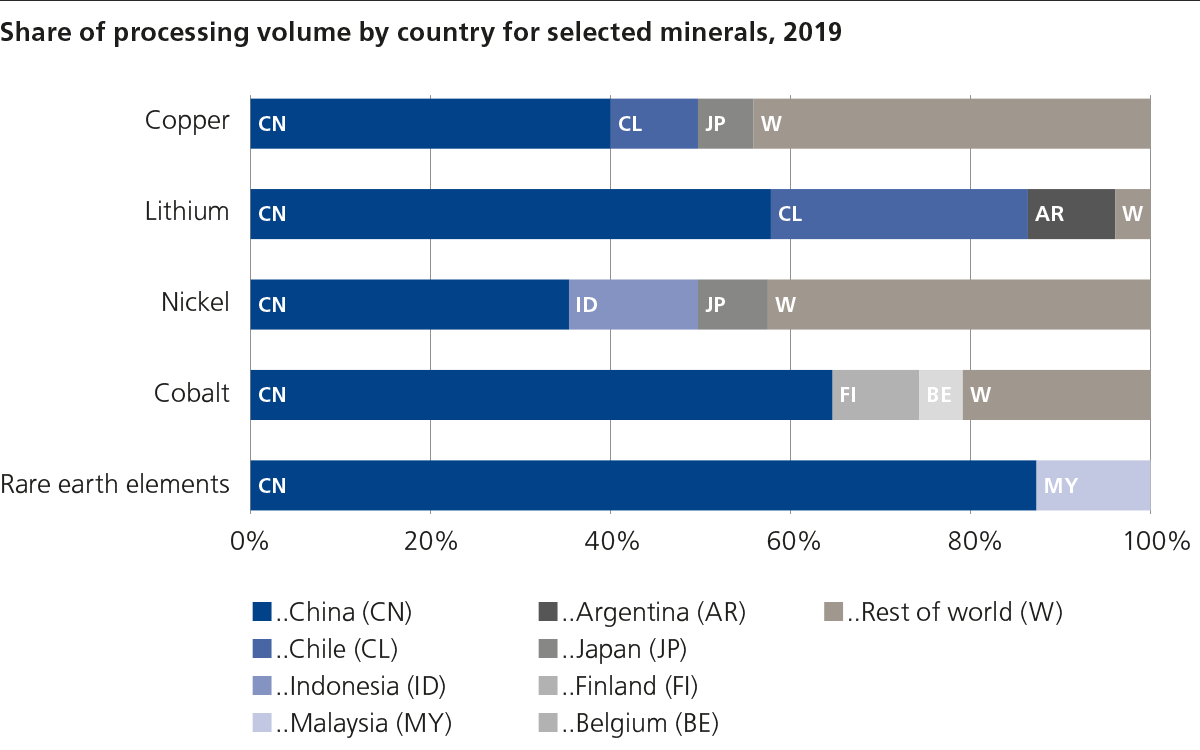

Another concern is that the processing of these materials is dominated by one single country: China. It processes 40% of global copper output, 60% of lithium, 70% of cobalt and over 80% of the rare earth elements. We have learnt many times before that over-reliance on other regions, particularly when they are a strategic competitor of yours, to process all your commodities can lead to unintended consequences. Energy security will need to go beyond reducing reliance on Russian gas and building renewable energy assets; it must also extend to the resources required within these necessary technologies.

In positive news, policymakers are already making steps towards creating greater certainty around supply chains. The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act is the prime example. The Act will help to ensure that the EU can create a strong, resilient and a sustainable value chain for these critical materials and increase the amount of processing done within the EU. This has benefits on several fronts:

This is also not to say that Western policies are perfect, but it can act as a powerful anchor for developing regions to understand what is expected from their key export markets from an ESG perspective and accordingly drive positive outcomes. What is still to be seen is what such policies will do to prices.

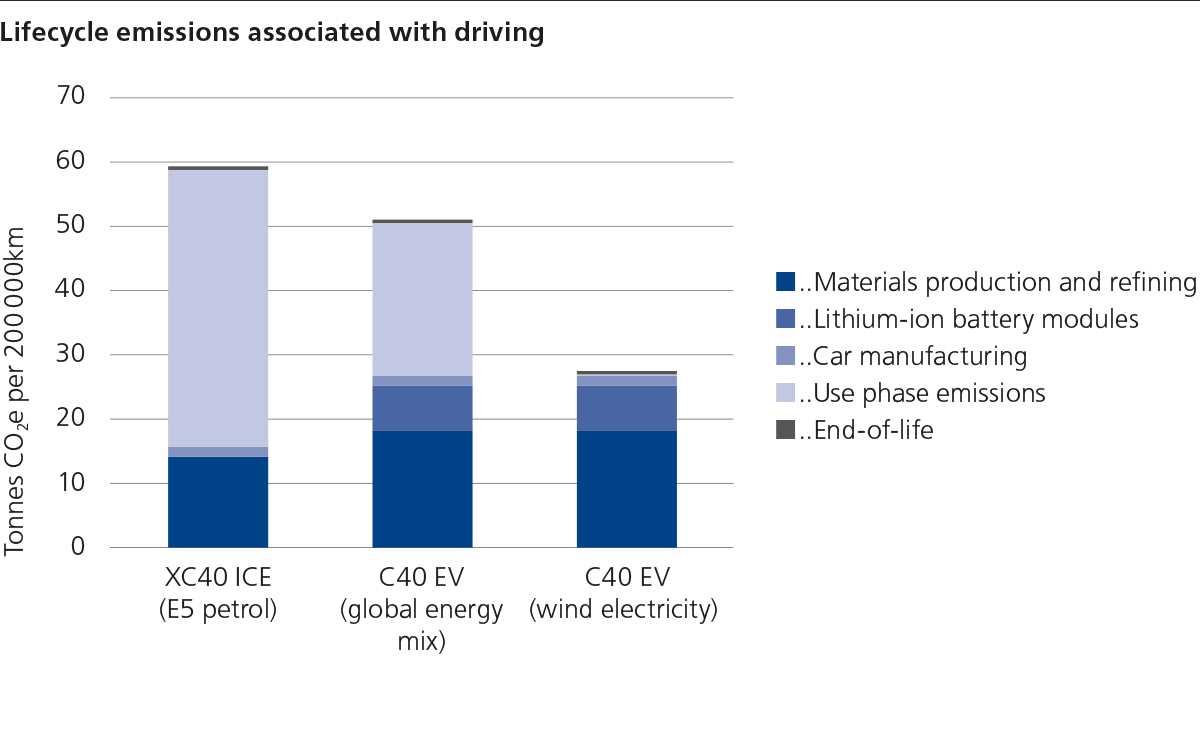

The shift towards a greener economy is critical, but the transition is not straightforward. Even an electric car (EV) comes with its own issues currently, as the increased usage of various materials comes with its own emissions and sustainability risks.

The diagram below highlights that a focus on the material inputs will be crucial in ensuring the sustainability and net-zero targets of heavy industry over the coming decades. This chart from Volvo highlights the high carbon intensity of current extractive processes. Even if you switch from a petrol to electric vehicle and source the electricity renewably, you are left with nearly half your emissions.

As shareholders, we have limited influence on governments and political instability, but companies can do more than you might expect. Large consumers of processed commodities have a large influence on the critical materials supply chains because they are the customers and, as we all know, the customer is always right!

The simple yet effective mechanisms that companies can implement is bolstering their requirements of suppliers to abide by strong environmental and social standards and, most importantly, to provide greater transparency around their practices. Companies that fail to prove that they are not causing significant environmental degradation or can’t prove they comply with global labour standards could end up losing key customers or lose their ability to sell their materials at attractive prices. We have seen the latter recently as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; Western sanctions on Russian oil meant they had to sell it to Asian countries at a deep discount.

Increasing regulations around carbon taxation, such as the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, will help to create greater competitiveness of commodities produced with lower carbon emissions. This helps to ensure materials produced with low carbon technologies can compete against materials produced with carbon intensive fuels, incentivising producers to decarbonise.

So, to answer the simple question, what can we do?

We should be looking for companies implementing stronger supplier conduct policies and use our voice as shareholders to engage with companies with significant exposure to critical material inputs.

We can also look to emerging technologies to help us along the way. For example, blockchain, the technology which underpins cryptocurrencies, is being touted to help certify and log supply chain conditions at every point from mine to grave or recycling.

We can also use our influence to push for greater sustainability across the commodity value chain through voting and engagement initiatives - Mining 2030 recognises the importance of the mining industry to the energy transition whilst also considering the systemic issues facing the mining industry.

It is fair to say there are plenty of ‘bad’ companies out there, but there are diamonds in the rough. The first example, Ivanhoe Mines, is primarily a copper miner operating in Democratic Republic of the Congo, one of the contentious regions we outlined earlier. Ivanhoe has set a strong precedent in the mining industry by focusing on geographies and deposits which require the least amount of environmental impact, powering facilities using onsite hydroelectricity and placing processing plants next to the mine, which significantly reduces the amount of material transported around the world. It has also affirmed its alignment with the United Nations’ Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, and conducts human rights impact assessments at its mining operations.

Further down the supply chain, we can also look to purchasers of these materials to have strong supplier standards and agreements in place. These standards may include third-party audits, ISO certifications (standards agreed internationally by experts) and other active commitments to ESG and sustainability criteria. Our second example is Wacker Chemie, a company operating in a regulated and complex chemical industry, which has established practices for supplier management. Its contracts specify quality checks and compliance with international standards. In addition to its contractual safeguards, Wacker Chemie emphasises ESG criteria in its supplier vetting process, which involves comprehensive audits, background checks and ongoing evaluations. This approach is consistent throughout the supply chain, from raw material sourcing to end-product delivery.

Whilst we need far more raw materials than that which has already been dug out the ground, it’s important to remember that commodities such as copper and aluminium, and many others, are infinitely recyclable – and it is increasingly cheaper to recycle than produce virgin material.

We know that your phone won’t be used forever, nor will the electric cars you see on the road. It is essential we continue to scale sufficient recycling facilities for these commodities and close the loop.

Like many of the issues we face as a global economy, most of the technology already exists - it just requires continued investment and the participation of high-quality companies to improve the economics and monetise it.

Our third example takes us to Europe where Umicore is based. The self-branded circular materials technology company is heavily involved in the recycling of critical materials including lithium, copper and nickel and is a leader in the recycling of rechargeable batteries used in EVs. It is also promising to see the company commit to an ambitious net-zero target for 2035. This example highlights that companies can generate strong growth (sales have grown at a compounded rate of over 16% over the past 5 years), improve circularity of critical materials and operate their business responsibly. The bar may feel high to some, but it is achievable whilst maintaining profitability if executed correctly.

No company is perfect and there is no such thing as the perfect sustainable company. With any company in any sector, we must look to establish minimum standards, allocate towards companies driving positive change and engage along the way to ensure companies are held accountable to their stakeholders.

All companies have a responsibility to effectively manage the risks that lie within their supply chains and we have a responsibility to hold companies to account where possible and exercise our rights as asset owners.

Burying our heads in the sand and avoiding contentious issues is neither responsible nor credible. We must maintain strong standards and expectations of the companies we hold on behalf of clients, directing capital towards companies driving the shift towards better practices in the commodities industry and beyond in order to achieve a credible energy transition.

This communication is provided for information purposes only. The information presented herein provides a general update on market conditions and is not intended and should not be construed as an offer, invitation, solicitation or recommendation to buy or sell any specific investment or participate in any investment (or other) strategy. The subject of the communication is not a regulated investment. Past performance is not an indication of future performance and the value of investments and the income derived from them may fluctuate and you may not receive back the amount you originally invest. Although this document has been prepared on the basis of information we believe to be reliable, LGT Wealth Management UK LLP gives no representation or warranty in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information presented herein. The information presented herein does not provide sufficient information on which to make an informed investment decision. No liability is accepted whatsoever by LGT Wealth Management UK LLP, employees and associated companies for any direct or consequential loss arising from this document.

LGT Wealth Management UK LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.