Climate change risks, and the need to transition to cleaner forms of energy, are widely recognised by governments, businesses, and consumers, but one part of the investment debate remains hotly debated – what role will oil and gas majors like BP play in the transition?

The answer, however, is not straightforward: although some oil and gas companies will successfully navigate the energy transition, it is naïve of us to assume outcomes in the fossil fuel industry will be homogenous.

Through history, we have seen how seismic industry shifts can lead to big and mostly unsuspected leadership changes. The mobile phone industry is a great example: Nokia, the once dominant phone maker, had a global market share of over 38% at its peak but, when the touchscreen phones came in, that quickly changed and now stands below 5% just 15 years on.

Whilst phones and energy are of course very different, this does highlight an important point – renewable energy and fossil fuel energy generation is fundamentally different.

We do not believe by any stretch of the imagination that the oil and gas industry are asleep at the wheel. We are seeing a number of companies invest in developing their renewable capacity and shift away from fossil fuels, but it is not happening at a fast enough pace across the industry. Whilst BP’s target of 50GW of renewable capacity by 2030 and Total Energies’ target of 100GW are both sizeable, companies such as Shell have set no such commitments and many companies (including BP) have reeled back on the size of their commitments following the feeding frenzy triggered by rising commodity prices resulting from the Ukraine conflict.

Some companies are certainly awake to the headwinds for fossil fuels and the requirement to invest in cleaner energy solutions, however they are all at different starting points and the path ahead is uncertain and potentially treacherous.

This is where those holding oil majors on the belief they will facilitate the energy transition for us must tread carefully. For example, BP has an installed renewables capacity of 2GW and Total Energies had 17GW at the end of 2022, which both represent a huge gap between the proven execution across oil majors, and between their current position and commitments. Here is the big risk:

Can they be competitive with new players such as NextEra and Ørsted who have already developed a strong track record in executing high quality renewables assets?

One argument we often hear is that renewables are heavily reliant on subsidies and would be unprofitable without such support. Whilst it is true that there are subsidies across the world to help encourage companies invest in the development of cleaner energy, it is not just wind and solar getting a helping hand - so are their fossil fuel counterparts.

Since 2015, the fossil fuel industry has received approximately £20 billion more in subsidies than renewables in the UK alone. When we account for undercharging for environmental costs, forgone consumption taxes and explicit subsidies, the fossil fuel industry received subsidies to the tune of $5.9trillion in 2020, or 6.9% of global GDP.

Further to this, the International Renewable Energy Agency estimated that the cost of unpriced externalities and direct fossil fuel subsidies exceeded renewable energy subsidies by a factor of 19. They also estimated that, of total energy subsidies, only 20% went to renewables.

One of the biggest potential risks to the fossil fuel industry is the internalisation of externalities – that is a fancy way of saying they will have to start paying for the damages they inflict on the environment and society as a result of their business activities.

This concept has been brushed off for many years, but the pendulum may now be shifting. In the US, the Supreme Court has allowed for lawsuits to be filed by municipalities seeking to hold companies liable for harm caused by carbon emissions. Already, we have seen Shell’s board be subject to a lawsuit due to their poor climate strategy and oil giants have been sued over climate change deception in the US state of Oregon to the tune of $1.5 billion.

One of the most effective mechanisms, which is being introduced around the world, is a carbon tax which follows the ‘polluter pays principle’ whereby companies will be charged for the carbon they emit. So, the big question remains:

What does the increasing level of environmental litigation and environmental taxes mean for the profitability of fossil fuel companies?

The answer to this is complex and still too hard to fully quantify, but some European oil and gas companies are paying up to 10% of operating costs in carbon taxes already. It is fair to say the direction of travel is not a positive one for oil majors balance sheets.

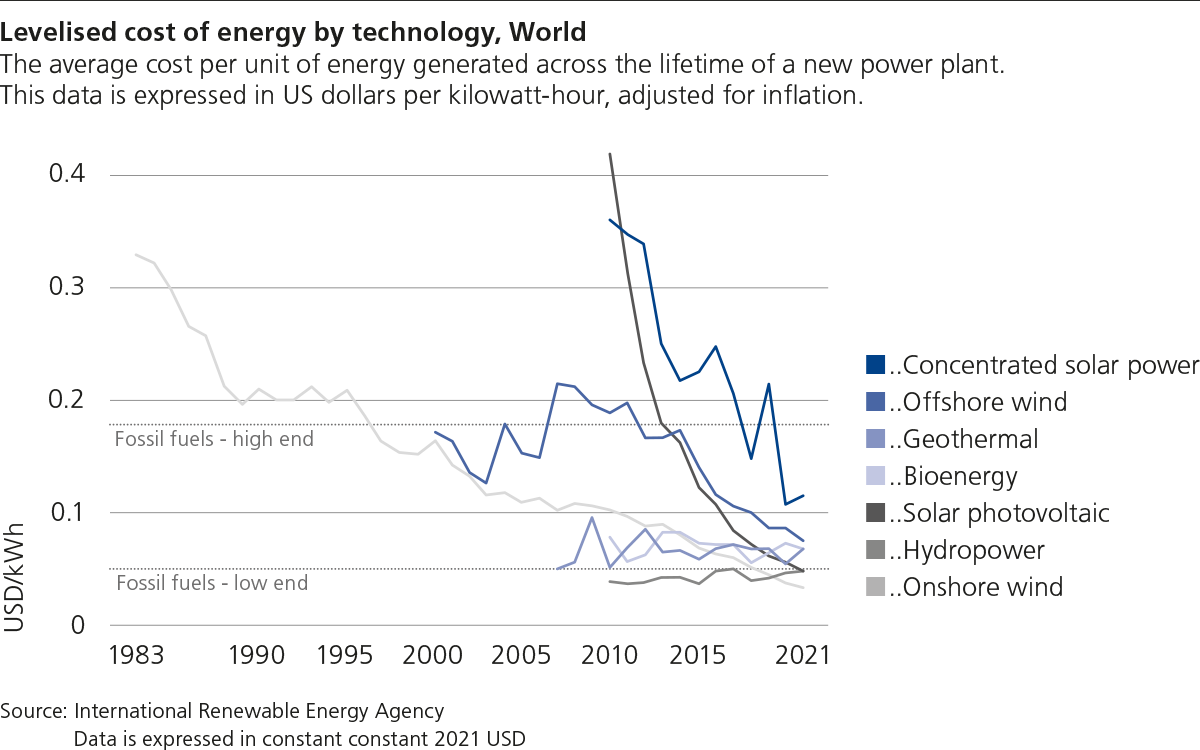

As a result of subsidies, heavy investment and falling costs for capital investment, the cost of renewable power has been on a rapid march lower for the past couple of decades to a point where large-scale wind and solar PV are the cheapest forms of energy generation globally and with less price volatility than fossil fuels.

However, due to increasing inflationary pressures across the labour and materials supply chain, costs have gone up, as they have for the whole energy sector. Whilst the average across the sector has increased, analysis from Lazard actually tells us that some of the larger players have actually continued to reduce costs due to technological advancements. It serves as a reminder that not all renewable companies will be able to navigate this difficult period of uncertainty - but we already knew that.

As a sustainability specialist, I believe that renewables are the future source of global energy demands, but it is important that we remain balanced and acknowledge that gaps remain, particularly around the intermittency of renewable power.

The main issues are that we have no control over when the wind blows and when the sun shines (particularly in the UK), and it is rare that high renewables generation coincides with peak energy demand.

More infrastructure is required to store excess energy to have on the side-lines for when the wind isn't blowing but everyone is still boiling the kettle in the evening.

Fortunately, all of the technology we need for this exists, including battery storage (electromechanical) and mechanical solutions such as pumped hydro which simply takes advantage of gravity. The problem is supply: not enough of this exists today. This tells us something else we already knew – we cannot simply switch from fossil fuels to renewables overnight. Whilst we do not yet have the answer to removing fossil fuel from every aspect of our energy system and economy, we do have most of them. Following the path of wind and solar, these ‘gap fill’ solutions are also becoming increasingly commercially attractive. This dynamic will help accelerate the transition over the years to come.

Our view is not that all fossil fuel companies are asleep at the wheel and the only companies that will exist in 10-20+ years will be the renewable companies we know of today. Our aim is to shed light on areas of the debate which are often ignored, and to provide a balanced view of where the energy transition stands today.

Rightly or wrongly, fossil fuels will make investors money (at least in the form of dividends) this year and the next. But we must question the economics of these fuels through the same lens we use to scrutinise the renewable energy sector. The direction of travel is clear, and we have no real way of understanding how much profits fossil fuel companies will be allowed to generate in a world where externalities are internalised. So how do we account for this when valuing such companies?

My optimistic side would like to believe that some will do an excellent job of transitioning their business model, as Ørsted has done over the past couple of decades, but relying on the kindness of strangers has seldom been a sure-fire way to make money. The final, and most important, question I will ask is: are investors comfortable with the quality and execution within renewables at the large oil companies?

This is a question that needs to be asked, because the risk of being left by the wayside cannot be ignored when investing for the long term. Will the likes of BP take a starring role, or will they fade to obscurity as new players emerge to take the plaudits? It is too early to tell, but we will be watching with interest to see how the debate plays out.

This communication is provided for information purposes only. The information presented herein provides a general update on market conditions and is not intended and should not be construed as an offer, invitation, solicitation or recommendation to buy or sell any specific investment or participate in any investment (or other) strategy. The subject of the communication is not a regulated investment. Past performance is not an indication of future performance and the value of investments and the income derived from them may fluctuate and you may not receive back the amount you originally invest. Although this document has been prepared on the basis of information we believe to be reliable, LGT Wealth Management UK LLP gives no representation or warranty in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information presented herein. The information presented herein does not provide sufficient information on which to make an informed investment decision. No liability is accepted whatsoever by LGT Wealth Management UK LLP, employees and associated companies for any direct or consequential loss arising from this document.

LGT Wealth Management UK LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.