For much of the past decade, software companies – which make everything from payments infrastructure and risk management systems to customer relationship platforms and accounting software – have been treated as one of the market’s highest quality assets. These companies sold access to intelligent digital tools that, once built, could be distributed to millions of customers at very low additional costs. For years, this allowed software companies to grow rapidly without the capital intensity of traditional industries, making them highly attractive to investors.

These characteristics led to predictable revenue streams and strong operating leverage, making software companies a reliable source of growth and cash generation. That predictability became a defining feature of the software investment case, one that is now under pressure, as artificial intelligence (AI) threatens to turn what were once scarce, high-margin software assets into ones that could potentially be replaced at a much lower cost.

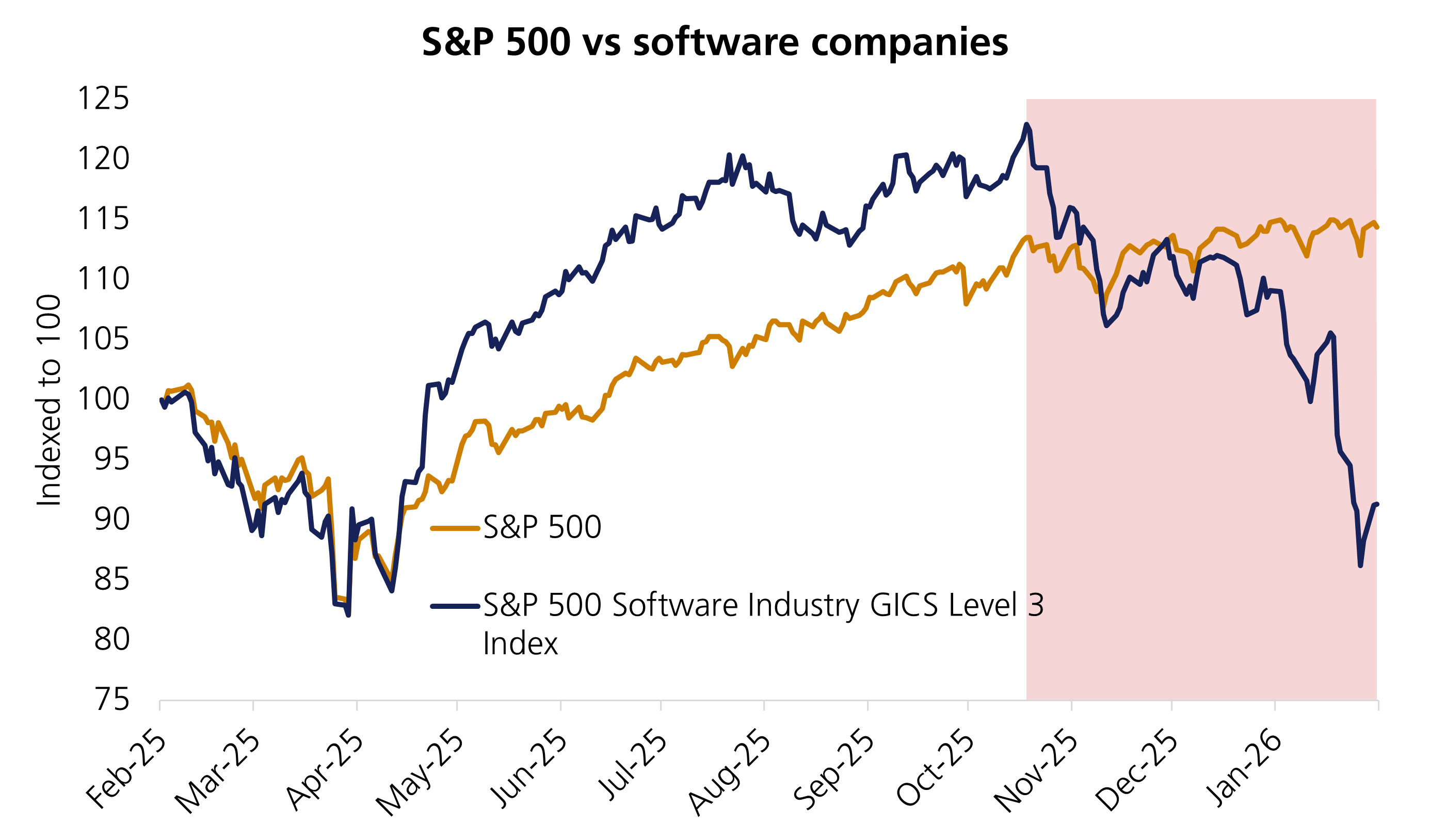

Last week, the release of industry-specific plug-ins for Anthropic’s new Claude Cowork tool – which uses natural language instructions to complete complex, multi-step work for users, including file organisation and document creation – triggered a broader selloff across software stocks, as investors became concerned that AI tools such as Claude could render traditional enterprise software-as-a-service (SaaS) companies redundant.1

The market response highlights how quickly narratives around disruption can take hold. Investors have been reassessing one key ingredient: the certainty of future cash flows. Concerns aren’t that growth has ended, but rather that the range of potential outcomes has widened considerably.

History is punctuated by rare technological breakthroughs that permanently reshape economies and societies – electricity, the light bulb and the internet are among them. AI may prove to be the next.

One of AI’s most immediate impacts has been on software development itself. AI tools can now write and debug code at speeds that would have seemed impossible just a few years ago. This means the time and cost of building software has rapidly fallen. The competitive advantage that software companies traditionally had from their huge piles of code developed over decades suddenly doesn’t seem so significant.

Amazon founder and Chairman Jeff Bezos once observed that he is often asked, “What’s going to change in the next ten years?” but rarely, “What’s not going to change?” The software companies most likely to endure are those built around needs that remain stable even as technology evolves.

This shift does not eliminate competitive advantage in software, but it changes where that advantage resides. Established software companies are often more resilient when they provide mission-critical systems or operate in areas with high regulatory complexity. In these cases, deeply embedded workflows and proprietary datasets strengthen customer relationships and raise switching costs, creating meaningful barriers to entry. These companies are also able to leverage these same AI tools to strengthen their positions.

Ultimately, in an AI-driven world, development cycles are now shorter and features that once differentiated a product can be replicated more quickly, intensifying competition across much of the software landscape. As in previous economic shifts and transitions, the impact will inevitably be uneven.

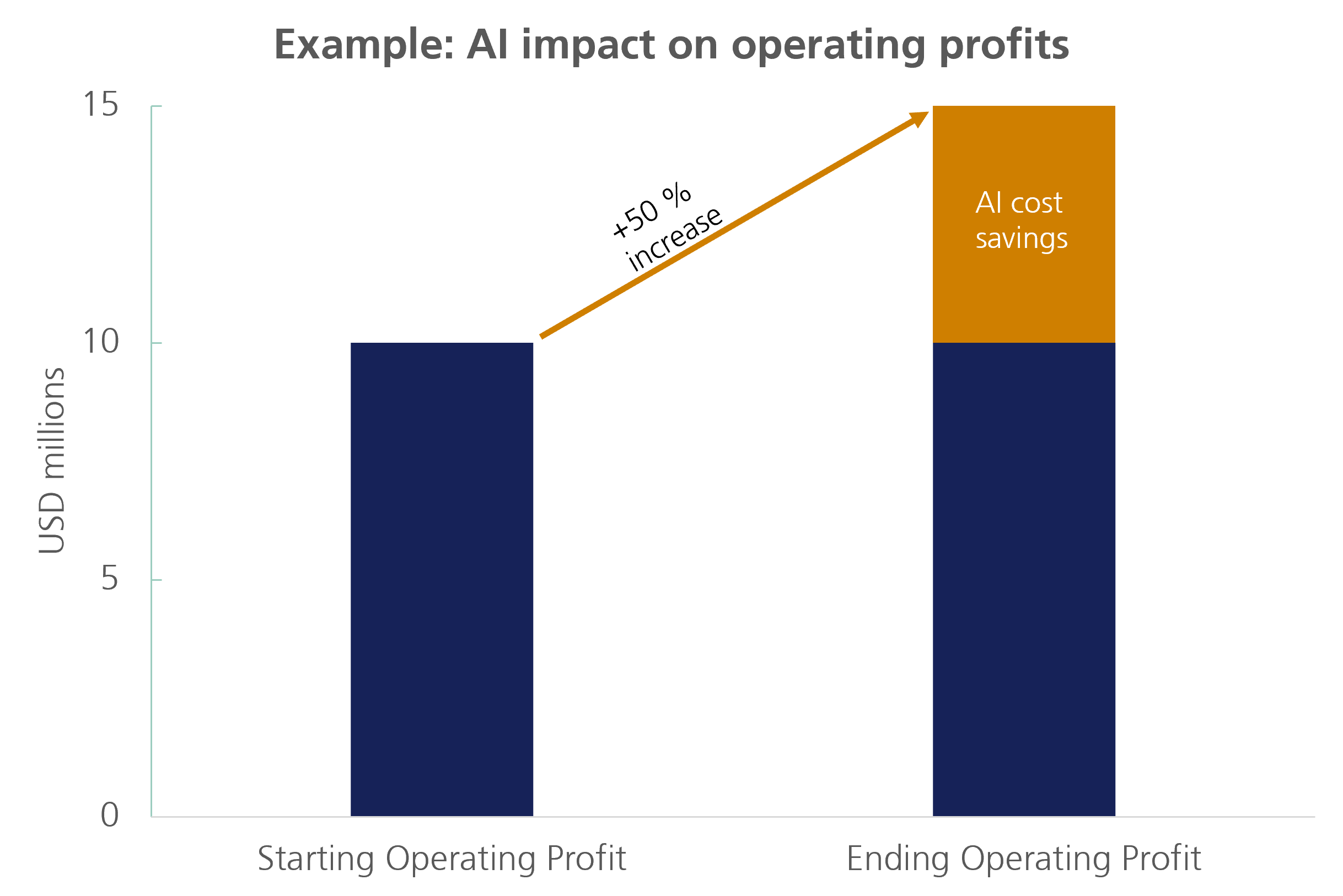

To be sure, the AI story is not only about disruption within software. Some of the most immediate and tangible beneficiaries of AI may sit outside of the technology sector altogether. Traditional businesses – distributors, manufacturers and service providers – can use AI to improve efficiency and reduce costs without facing the same competitive pressures now intensifying across software companies.

Consider a mid-sized distributor of industrial equipment. Historically, inventory management required staff physically walking around the warehouse, payroll processing employed two full-time workers and customer service relied on a team of five. With AI handling inventory optimisation, automating payroll processes and managing routine customer enquiries, the same business can operate with half the administrative headcount. Operating margins that once sat at 10% could potentially rise to around 15% – resulting in a 50% increase in profitability – without selling a single additional unit. The business has not grown, but it has become meaningfully more profitable.

Software remains a powerful and indispensable part of modern economies and investment portfolios, but the sector is entering a more competitive and uncertain phase. The competitive advantages, once assumed to be almost impregnable, may prove narrower than previously thought, as AI reshapes how software is built, differentiated and priced.

For investors, this shift demands greater selectivity. Dispersion within the sector will likely rise as markets distinguish more clearly between businesses with durable cash-flow visibility and those facing heightened uncertainty around pricing power and margins. Understanding not just what a company builds, but how it is used, how easily it can be replaced and how critical it is to customers’ operations will be essential.

Quality still matters in software – but in the age of AI, their services face the greatest potential replacement risk. This will make investors question the resilience of these business models for some time to come.

[1] Why Anthropic’s new Claude plugins sparked global selloff in software stocks — TradingView News

This communication is provided for information purposes only. The information presented herein provides a general update on market conditions and is not intended and should not be construed as an offer, invitation, solicitation or recommendation to buy or sell any specific investment or participate in any investment (or other) strategy. The subject of the communication is not a regulated investment. Past performance is not an indication of future performance and the value of investments and the income derived from them may fluctuate and you may not receive back the amount you originally invest. Although this document has been prepared on the basis of information we believe to be reliable, LGT Wealth Management UK LLP gives no representation or warranty in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information presented herein. The information presented herein does not provide sufficient information on which to make an informed investment decision. No liability is accepted whatsoever by LGT Wealth Management UK LLP, employees and associated companies for any direct or consequential loss arising from this document.

LGT Wealth Management UK LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.