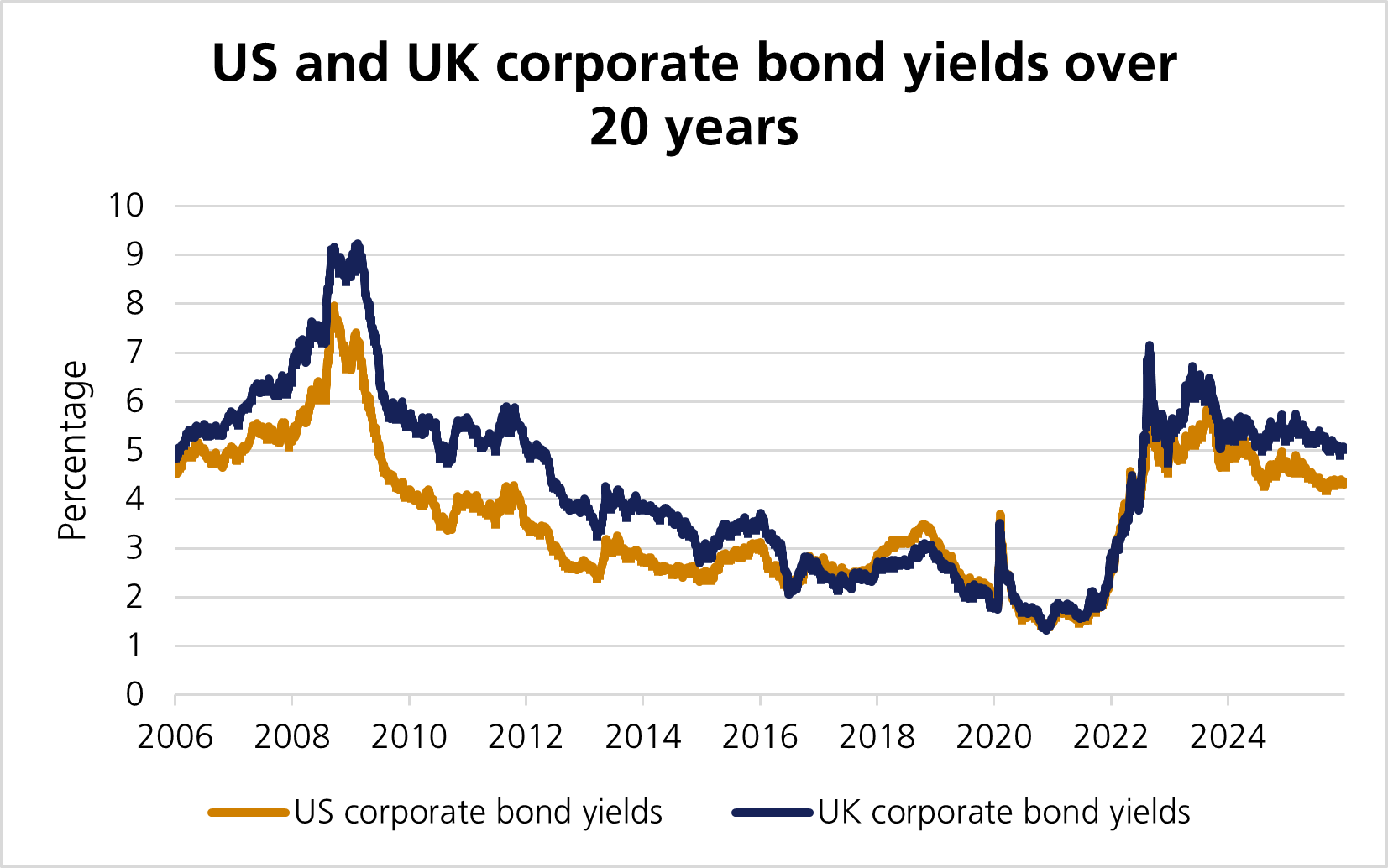

In the decade following the 2008/09 global financial crisis, fixed income investors generated meaningfully higher returns from corporate bond exposure than government bond holdings. Central banks kept interest rates close to zero for much of this time, and in some cases, even resorted to negative interest rates, which meant government bond yields – the annual income investors receive for lending money to governments – were extremely low, offering limited income. Corporate bonds, by contrast, paid higher interest to compensate investors for taking additional risk, and therefore became an important source of returns within fixed income portfolios.

Over this period, markets were supported by quantitative easing, or QE – when central banks make large-scale bond purchases to support the economy by keeping borrowing costs low. While this pushed government bond yields even lower, it also drove bond prices higher. In other words, buying bonds made them more expensive, which helped investors who already held them. These effects spilled over into corporate debt, providing a powerful tailwind for fixed income markets overall at a time when investment banks were retreating to rebuild capital buffers and shore up their balance sheets.

In recent years, the dynamic has reversed as central banks responded to the highest inflation seen in a generation. Interest rates were raised sharply, and the extraordinary policy support of the previous decade began to unwind. Central banks not only stopped buying bonds, but actively reduced their holdings through a process known as quantitative tightening, or QT. In simple terms, QT means central banks are allowing bonds to mature without replacing them or selling them outright – reducing a key source of support for bonds.

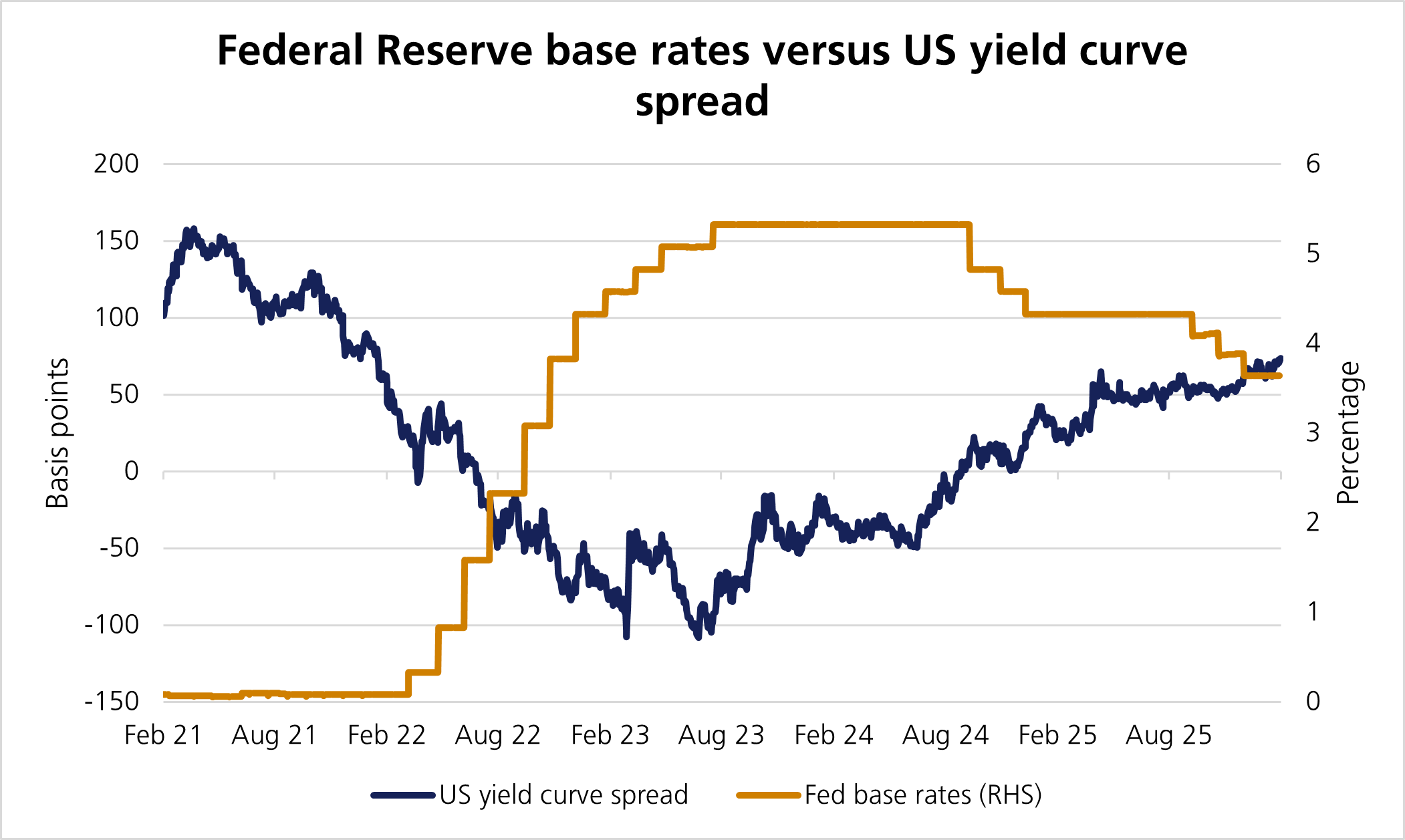

As the interest-rate hiking cycle progressed, yield curves – which plot interest rates of bonds with different maturities – moved from positive territory into inversion. In a normal environment, longer-dated bonds pay more than shorter-dated ones because investors are taking on more risk. An inversion in the yield curve occurs when this relationship flips – short-term interest rates rise above long-term rates, signalling that investors believe borrowing costs are unusually high and unlikely to persist.

Many investors viewed elevated interest rates as a temporary response to bring inflation under control rather than a permanent shift. As a result, markets began to price in expectations that interest rates would eventually fall again as inflation eased and economic conditions improved.

As inflation moved closer to central banks’ targets, policymakers gained greater scope to cut interest rates. At the same time, concerns about rising government borrowing – combined with central banks reducing their holdings of government bonds through QT – led investors to reassess the compensation required for holding longer-dated government debt. This pushed the so-called term premium – the additional return investors demand for lending to governments over longer periods to compensate for inflation and fiscal risks – higher.

Meanwhile, higher interest rates prompted many companies to reassess their reliance on debt financing. In aggregate, corporate borrowers reduced indebtedness to reflect the higher cost of borrowing. Combined with relatively solid global growth, corporate balance sheets are now in a healthy position. As a result, investors require less additional compensation to hold corporate bonds relative to government bonds, pushing credit spreads – the extra yield corporate bonds pay over government bonds – to levels last seen decades ago. In other words, companies look financially healthy, but investors are no longer being paid much extra for taking corporate credit risk. While compensation is moderate, the overall yields available remain relatively high compared to the last two decades.

Shorter-dated government bond yields have fallen from their recent highs during the rate cutting cycle. This, paired with low corporate bond spreads, has prompted investors to reassess where value now lies within fixed income and how best to generate excess returns. With term premia having risen, investors are once again being compensated for committing capital for longer periods.

The resulting upward-sloping yield curve means investors can earn additional returns simply by holding a bond as it moves closer to maturity and gradually “rolls down” the yield curve – a phenomenon known as roll-return, which occurs when a bond’s price increases as it approaches its maturity date and moves into a lower-yielding part of the curve.

Capturing this return depends on term premia remaining broadly stable. If yields do not rise further, investors can benefit from both the income earned and the price appreciation that occurs as bonds move closer to redemption. The same principle can apply within corporate bonds, where extending maturity along a company’s yield curve can offer an additional yield pick-up.

While bonds can provide income and diversification, investors should be aware that fixed income investments carry risks. Rising interest rates can reduce bond prices and spreads could widen if economic conditions deteriorate, which could lead to some companies defaulting. Liquidity concerns may push spreads wider as well, while term premia could increase if fiscal concerns become acute. The combination of these factors means that while fixed income can provide stable income, investors can experience capital losses and fluctuations in value.

While corporate bond spreads are tight and yields have fallen from recent highs, bonds remain a meaningful source of income. Even if yields aren’t as high as they were, fixed income still provides predictable income for investors. That return can be enhanced by using strategies that focus less on credit risk and more on capturing the roll-return along the yield curve.

This communication is provided for information purposes only. The information presented herein provides a general update on market conditions and is not intended and should not be construed as an offer, invitation, solicitation or recommendation to buy or sell any specific investment or participate in any investment (or other) strategy. The subject of the communication is not a regulated investment. Past performance is not an indication of future performance and the value of investments and the income derived from them may fluctuate and you may not receive back the amount you originally invest. Although this document has been prepared on the basis of information we believe to be reliable, LGT Wealth Management UK LLP gives no representation or warranty in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information presented herein. The information presented herein does not provide sufficient information on which to make an informed investment decision. No liability is accepted whatsoever by LGT Wealth Management UK LLP, employees and associated companies for any direct or consequential loss arising from this document.

LGT Wealth Management UK LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.