Following the global financial crisis of 2008, some European countries faced mounting concerns over their own solvency. Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain – dubbed PIIGS by investment bankers – struggled with weak economic output, substantial debt levels and overleveraged banking systems. These factors, fuelled by excesses from the previous decade following the adoption of the single currency, the euro, sparked fears these nations would default on their debt. It ultimately led leading to the Eurozone crisis of 2010-2012, with Greece eventually requiring a bail out.

Among these countries, Italy stands out – not only for its economic vulnerabilities but also for its chronic political instability. Italy has had a long history of political upheaval, having had over 60 governments since World War II. Some were concerned when Giorgia Meloni of the right-wing Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy) became prime minister in 2022, she would be a disruptive force in the EU and hinder efforts to find consensus among leaders.

However, Meloni has proven to be a beacon of stability for Italy while improving its fortunes, largely because her coalition agreements have remained intact for nearly three years. During her first European Council summit, Meloni made it clear she was somebody the other 26 leaders could work with.1 She has positioned herself as pro-Ukraine while aligning with Europe on foreign policy.

Meanwhile, France – the Eurozone’s second-largest economy – seems to have swapped places with Italy as the country has been plunged into political turmoil. While President Emmanuel Macron has retained his position, he has recently overseen the resignation of a prime minister after just 26 days in office – only to be reinstated four days later – and his third in just over a year.

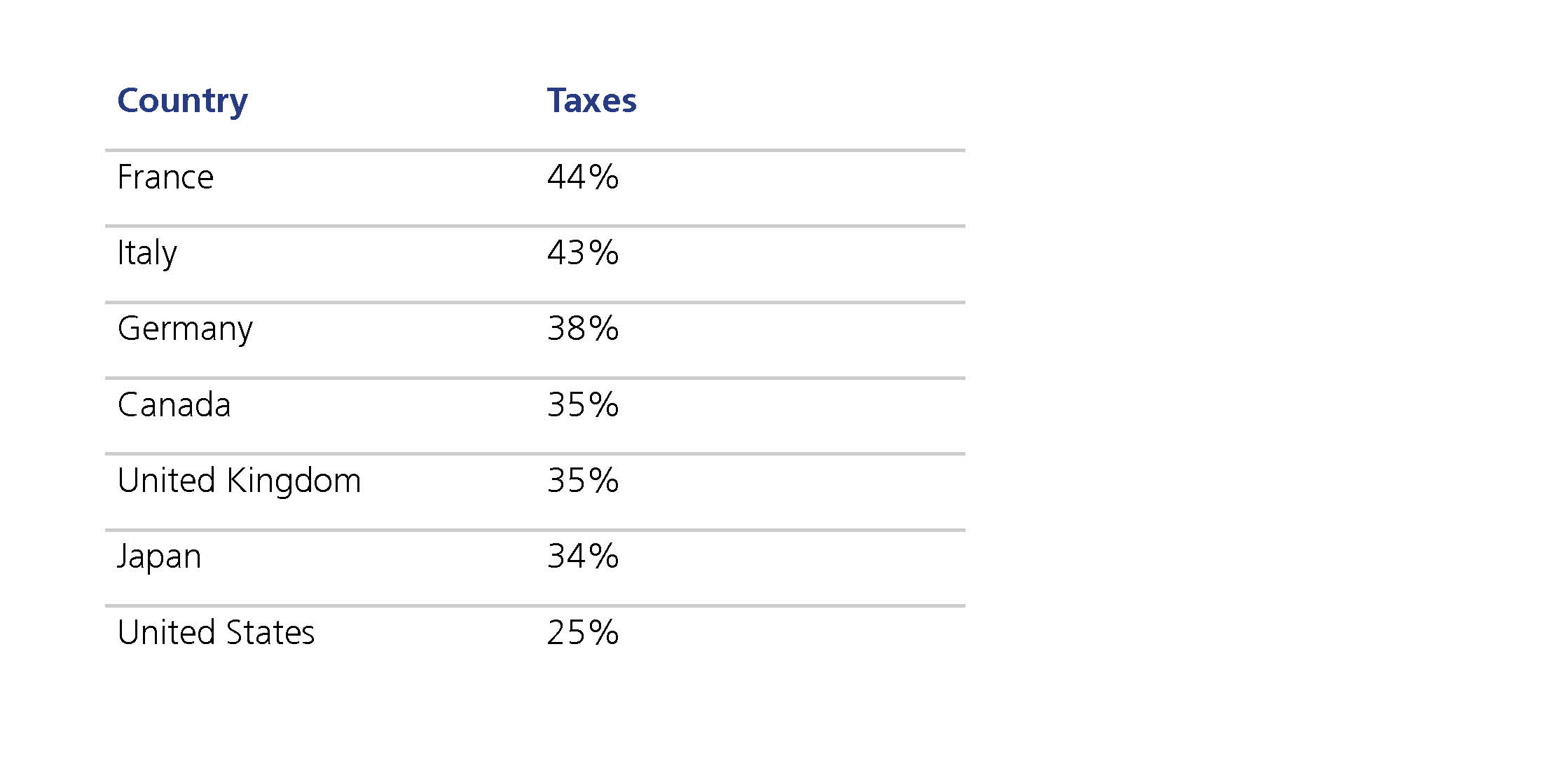

France faces ballooning debt and its citizens already pay some of the highest taxes in the world (see table below), limiting the government’s ability to raise taxes further. Investors are now asking whether these constraints are making France increasingly ungovernable.

France borrowed substantially during the pandemic and is now sitting on €3.4 trillion worth of debt while looking at a projected budget deficit of 5.4% of GDP this year. This is an unsustainable path for a country which has grown by 0.8% (2.5% in nominal terms)1 over the last year to June.

Cutting spending is particularly challenging in France, where pensions and healthcare make up the largest part of government expenditure amid an aging population. In addition, Paris has committed to spending on reindustrialisation, transitioning to green energy and strengthening its military capabilities following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.2

To understand the current turmoil in French politics, it’s worth taking a step back to June 2024.

On 9 June 2024, Macron’s centrist party came second to Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally in the European elections.3 The result was not a surprise – polls had predicted a National Rally victory – but Macron’s actions were. He announced that evening he would dissolve parliament and call snap elections, an attempt to try to block the far right’s seemingly unstoppable rise. It was an unprecedented gamble that resulted in a hung parliament roughly divided in three equal blocs, with most unwilling to engage in coalitions.4

Michel Barnier was the first prime minister to attempt to slash the budget after Macron’s snap election. Barnier lasted about three months when his plan to cut billions in public spending failed to pass. François Bayrou took over and lasted nine months before resigning over his budget, which included proposals to cut two public holidays. Sébastien Lecornu took over in September and resigned after just 26 days5, although he was reinstated as prime minister only four days later. On 16 October, Lecornu survived two no-confidence votes after separate motions were lodged against him. He now has his work cut out for him, including finalising the 2026 budget in a fragmented National Assembly in which his party does not have a majority.6

This revolving door of French prime ministers underscores how difficult it is for governments to cut budgets in developed economies.

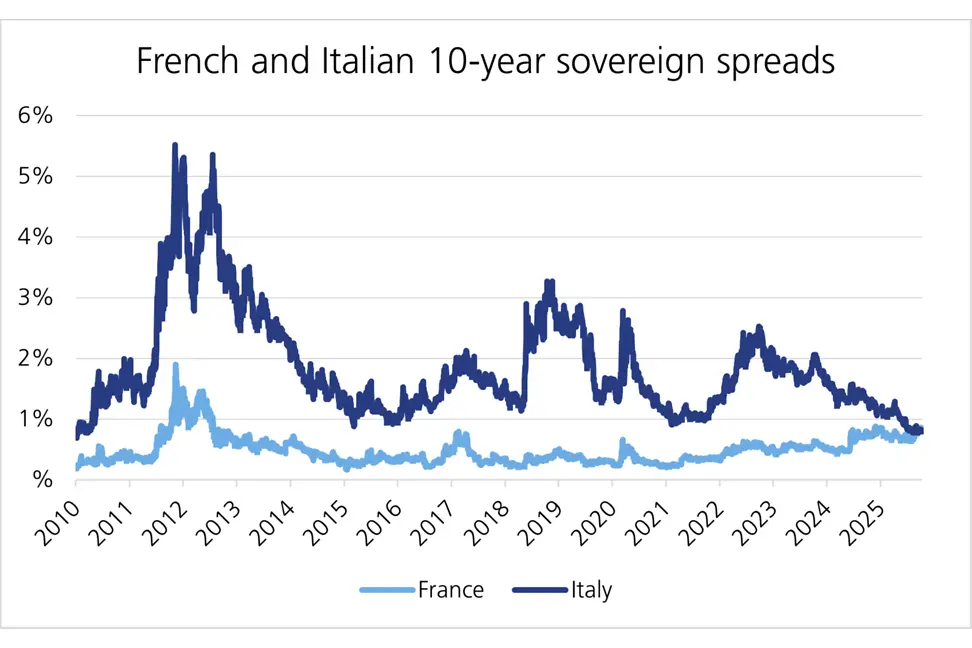

While the spread between French and German debt has risen markedly, it is still far from levels that Italy faced during the Eurozone crisis. Notably, Italian and French government bonds are now trading at similar levels, highlighting how investors’ perception has changed over the past decade.

While France’s ongoing political turmoil is unsettling, particularly as fiscal concerns mount, it is important to note that France remains one of the wealthiest nations in the world. It is one of the largest economies in Europe with strong institutions. Despite the recent string of short-lived governments, the state is still functioning, and bond markets have not shown acute signs of major stress.

Budget deficit levels are high, but this is not without precedent. The entire Western world is coming to terms with aging populations and rising costs of maintaining welfare states. This issue is broader than France, but reforms will be necessary in the medium term to reassure investors. France’s broad energy independence, with its large nuclear power capabilities, has been an advantage relative to Germany’s reliance on gas imports.

It is also worth noting that political instability does not necessarily lead to fiscal chaos. Italy, after being caught up in the Eurozone crisis and enduring frequent changes in government, has emerged stronger. Markets adapt, coalitions are formed, and institutions – particularly in advanced economies like France – prove more resilient than headlines suggest. While frequent prime minister resignations can stall or complicate the budget process in France, funding typically continues under the existing budget. New or discretionary spending may be stalled, but essential services remain funded. While not as aggressive as the US shutdown mechanism, there are protections in place.

While political turbulence continues in the Eurozone, shifting from southern nations to northern countries, its endurance is not being questioned. France’s woes will continue to simmer in the background, but its commitment to the Eurozone will be of comfort to investors.

[2] Nominal growth refers to data not adjusted for inflation, the same as budget deficits

[3] What to know about France’s political mess – POLITICO

[4] EU elections 2024: Results and the new European Parliament - House of Commons Library

[5] What to know about France’s political mess – POLITICO

[6] French Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu resigns after less than a month - BBC News

[7] French PM Sébastien Lecornu survives two no-confidence votes by MPs - BBC News

This communication is provided for information purposes only. The information presented herein provides a general update on market conditions and is not intended and should not be construed as an offer, invitation, solicitation or recommendation to buy or sell any specific investment or participate in any investment (or other) strategy. The subject of the communication is not a regulated investment. Past performance is not an indication of future performance and the value of investments and the income derived from them may fluctuate and you may not receive back the amount you originally invest. Although this document has been prepared on the basis of information we believe to be reliable, LGT Wealth Management UK LLP gives no representation or warranty in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information presented herein. The information presented herein does not provide sufficient information on which to make an informed investment decision. No liability is accepted whatsoever by LGT Wealth Management UK LLP, employees and associated companies for any direct or consequential loss arising from this document.

LGT Wealth Management UK LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.